Behind the Gloss: Why Selling $20 Million Worth of Indie Games Still Isn’t Enough

I’ve spent enough time surfing the web to notice a recurring fantasy: people fed up with their jobs or studies, dreaming of ditching the grind to pursue their passion—making games.

“What if I quit my job or dropped out to develop games?”

they wonder, imagining a life of creativity and freedom. Compared to those who jump headfirst into opening a brick-and-mortar business with little knowledge and a heavy cash flow burden, game development seems less risky. After all, you can do it from home, and the upfront costs aren’t as daunting. But that’s just scratching the surface.

The reality is, the game industry is fiercely competitive. For newcomers, the journey from zero to survival—or even a modest breakthrough—is long and uncertain.

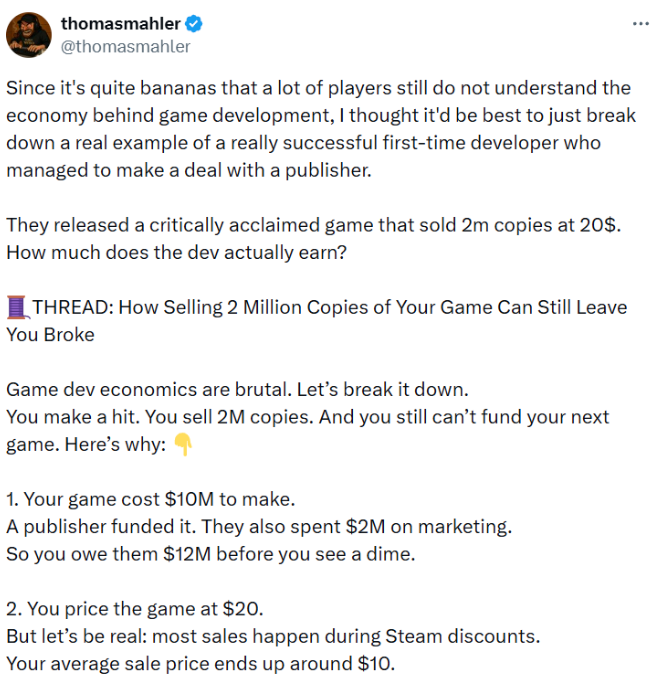

Recently, Thomas Mahler, founder of Moon Studios GmbH, took to X to break down the harsh economics behind making money with games. He wanted to clear up the confusion many players have about what really happens when a game “succeeds.”

Let’s dissect his case study: Imagine a first-time developer lands a publishing deal and sells 2 million copies of their game at $20 each. How much do they actually make?

Here’s the brutal math:

- Development costs: $10 million, plus $2 million for marketing (fronted by the publisher). Before you see a dime, you owe them $12 million.

- Game price: $20, but most sales come from Steam discounts. The real average price is closer to $10.

- 2 million copies sold = $20 million in gross revenue.

- Steam takes a 30% cut. That leaves $14 million.

- The publisher recoups their $12 million investment first. The developer’s share so far? Zero.

- The remaining $2 million is split 70/30: the publisher gets $1.4 million, the developer $600,000.

- Subtract engine licensing fees (about $15,000) and taxes (roughly 50%). The developer’s final take? Around $292,500.

- So after selling 2 million copies, the developer has $292,500 in the bank. But the next game will still cost $10 million to make. That means they’ve only saved 2.9% of what they need.

- The indie creator’s dilemma: Success ≠ financial freedom. Platform fees, discounts, recouped costs, revenue splits, and taxes all eat away at profits, trapping developers in a vicious cycle.

- Want to self-fund your next project? Unless your current game sells even better, holds its price, or you publish independently, you’re stuck in the same loop.

The bottom line: 2 million copies, $20 million in gross sales, but just $292,500 ends up in the developer’s pocket. Behind the glamorous facade, indie game development is a tough business. Stay sharp. Stay independent—if you can.

Is Thomas exaggerating? Hardly. He’s a veteran in the industry, originally trained in sculpture before working on visual effects at Blizzard. He later co-founded Moon Studios GmbH with tech expert Gennadiy Korol, creating the critically acclaimed “Ori and the Blind Forest” and “Ori and the Will of the Wisps.”

The “Ori” series is beloved for its art, music, and boss battles. The first game sold for $20, making Thomas’s scenario a fitting parallel. “Ori and the Blind Forest” took four years to develop. If Thomas had $10 million in funding, that’s about $200,000 per month. For a 40-person team, that’s $5,000 per person per month; for 80 people, just $2,600. And that’s before factoring in equipment, insurance, benefits, and bonuses (the studio operates remotely).

Given that programmers’ salaries—especially abroad—often exceed these figures, $10 million for four years with 80 staff is a tight squeeze.

When the game finally ships and sells 2 million copies, the math plays out just as Thomas described. Without fresh investment or loans, keeping the team afloat is nearly impossible.

Why emphasize the 80-person team? According to reports, Moon Studios had over 80 employees by March 2020. In reality, though, “Ori and the Blind Forest” was built by a much smaller group; the sequel expanded the team. Combined, the two games have sold over 15 million copies, so Thomas’s own situation isn’t quite as dire as his example. Still, the point stands: even blockbuster success doesn’t guarantee financial stability.

After years of work, Moon Studios’ latest title, “No Rest for the Wicked,” had a rocky launch, prompting Thomas to plead with players online to give it a chance. Negative reviews threatened to sink sales and leave the studio strapped for cash. Fortunately, after several updates, the game’s reputation improved, but it’s clear: to keep a studio alive, you need to consistently release new, well-received games.

Why did Thomas bring up this topic? It may have been sparked by a recent article discussing Valve’s revenue share policies. Thomas shared the piece, arguing that a 30% cut is excessive for small developers—Apple and other platforms do the same.

The article notes that while Steam offers a lower 20% rate to major developers (those earning over $50 million), small studios bear the brunt of higher costs, making real profits elusive. Epic Games has tried to challenge Steam’s dominance with a 12% fee and a $1 million revenue exemption in the first year, but Steam’s massive user base keeps it on top. This “digital platform hegemony” forces developers to accept steep fees.

The author suggests Valve should lower fees for indies or risk legal intervention, and reviews the history behind the 30% standard.

In summary, even industry veterans admit that making money in games is hard. If you’re thinking about jumping in just for fun, think twice. Even small projects, like my own “Scratch Card Simulator,” require minimal resources, and I’m always wary of losing money.

Good night.