The Deadline Within: A Report on Procrastination

Byline: jack miller

Date: September 2, 2025

On a Tuesday afternoon at a therapy clinic affiliated with Stanford University, a software engineer named Michael describes his relationship with a project-management tool called Asana. “It’s a graveyard,” he says. “I open it, I look at the overdue tasks, and I feel a wave of—not panic, but a kind of static. A dull dread.” The tasks are not monumental: “Deploy Q3 Update,” “Draft Performance Reviews.” Yet for weeks, he has avoided them. Instead, he finds himself drawn into what he calls “virtuous rabbit holes”—optimizing his computer’s operating system, reorganizing digital files, or researching coding languages he has no immediate plans to use. He works ten-hour days, feels perpetually busy, and produces almost nothing of substance.

Michael is one of an estimated twenty percent of American adults who are chronic procrastinators. This is not the benign delay of putting off laundry for a day, but a self-defeating pattern of behavior that consistently undermines one’s personal and professional goals. “We are treating an epidemic of paralysis,” Dr. Elena Vance, the clinical psychologist leading Michael’s group, tells me. “And the conventional wisdom—that these are lazy or undisciplined people—is not only wrong, it’s destructive.” The modern understanding of procrastination, supported by a growing body of research, reframes it not as a character flaw or a failure of time-management, but as a visceral, protective response to negative emotions. It is, at its core, a problem of emotional regulation.

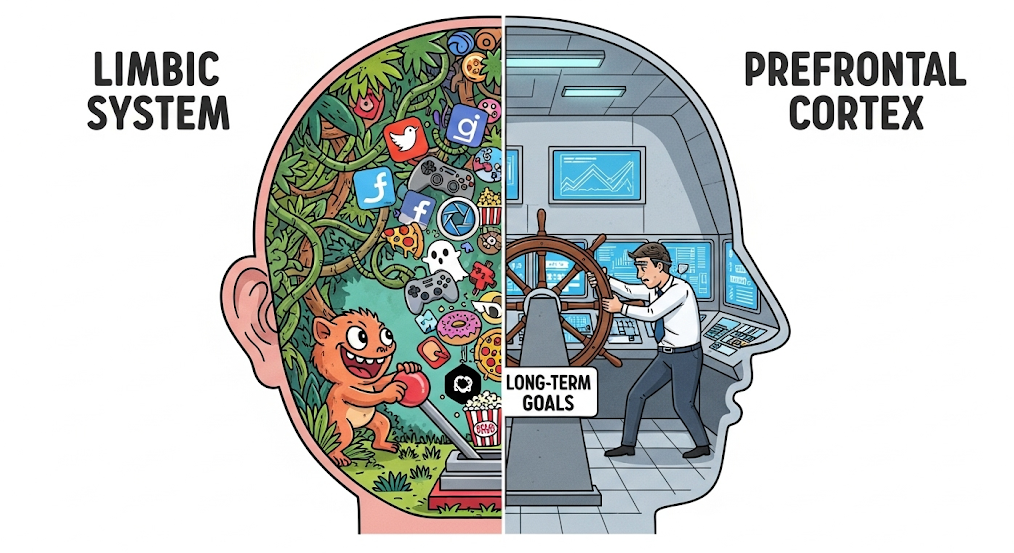

This idea has been most clearly articulated by researchers like Dr. Tim Pychyl of Carleton University and Dr. Fuschia Sirois of Durham University. Their work demonstrates that when faced with a task that induces feelings of anxiety, boredom, or self-doubt, the brain’s limbic system—its ancient, emotional core—overrides the rational planning of the prefrontal cortex. As Sirois outlined in a key 2013 paper in the journal Psychological Science, this leads to a decision to prioritize short-term mood repair over long-term goals. The brain chooses the immediate relief of watching a YouTube video over the anticipated discomfort of tackling a complex report. “It’s a profoundly human, if maladaptive, coping strategy,” Vance explains. “You’re not avoiding the task. You’re avoiding the feeling of the task.”

This emotional drama plays out on the most public of stages. For thirteen years, as of this fall, fans have been waiting for George R.R. Martin to publish The Winds of Winter, the sixth novel in his series A Song of Ice and Fire. The delay has become a cultural meme, a sort of shared public waiting game. In a rare public comment on his progress in late 2024, Martin admitted on his website to feeling the “enormous pressure” of the book’s legacy, which was cemented by the HBO adaptation, Game of Thrones. The task is no longer just writing a book; it is defending a cultural monument from its own creator. Every word must carry the weight of a decade of expectation. Viewed through the lens of emotional regulation, Martin’s delay is not simple idleness. It is a protracted, high-stakes negotiation with the fear of inadequacy. To avoid that fear, he engages in other, less emotionally fraught work—a classic pattern of avoidance.

The same paralysis, stripped of the celebrity, is a quiet crisis in academia. Before she left her doctoral program in history at the University of Texas at Austin, a woman named Sarah Connell spent eighteen months on the first chapter of her dissertation. She had won fellowships and was considered a rising star in her field. But the dissertation represented a final judgment. In a series of interviews, Connell described her state of mind at the time as a debilitating mix of perfectionism and what psychologists call Impostor Syndrome—the persistent fear of being exposed as a fraud.

“I’d sit down to write and my mind would just go blank,” Connell recalls. “All I could hear was the voice of my adviser critiquing a sentence I hadn’t even written yet.” To manage the anxiety, she would retreat into the archives, spending weeks chasing down a single, minor footnote. This wasn’t research; it was hiding. The act of infinite preparation created the illusion of work while protecting her from the risk of producing a flawed draft. “The unfinished dissertation remained a work of potential genius,” she says, with wry self-awareness. “A finished one would just be… mine. With all its faults.” Her story is not unique. Data from the Council of Graduate Schools shows that the completion rate for doctoral programs in the humanities within ten years is only around fifty-six percent; many of the non-completers drop out during the dissertation phase, a period psychologists identify as a crucible for perfectionism-fueled procrastination.

While the stakes for a novelist or a doctoral candidate are exceptionally high, the underlying mechanism is identical to the one that prevents most of us from tackling more mundane tasks. Sorting tax documents, making a difficult phone call, or starting a new exercise regimen can all trigger feelings of boredom, resentment, or self-doubt. Our response is often to bargain with a fictional, more capable version of ourselves. “Future Me will have more energy for this,” we tell ourselves. This cognitive bias, the unfounded optimism about our future emotional and motivational states, allows us to pass the buck to a version of ourselves who never seems to show up.

The digital architecture of modern life is a powerful accelerant for this cycle. The internet provides a frictionless escape into a world of immediate, low-stakes rewards. “Our phones are basically portable procrastination machines,” says Dr. Vance. The attention economy is built on the same neurological loop that drives procrastination: a trigger (a notification), a behavior (clicking), and a reward (a novel piece of information or social validation). This trains the brain to constantly seek out distraction, weakening what psychologists call our “executive functions”—the very skills of planning, focus, and self-control needed to combat procrastination.

The personal cost of this chronic avoidance is far greater than missed deadlines. Research, including a 2015 meta-analysis led by Dr. Sirois, has linked chronic procrastination to a host of health problems, including higher levels of stress, anxiety, depression, and even hypertension. The constant, low-grade stress of unfinished tasks and the corrosive guilt that accompanies it take a physical toll. Internally, it creates a crisis of self-trust. Each time we break a promise to ourselves, we reinforce a debilitating narrative: that we are incapable, that our goals are beyond our reach.

Breaking this cycle requires a radical shift in approach, away from self-criticism and toward mindful self-awareness. “You cannot shame yourself into productivity,” Vance states emphatically. In fact, her clinical work builds on the findings of Kristin Neff, a researcher at the University of Texas at Austin, whose work on self-compassion has been shown to be a powerful antidote to the shame spiral that fuels procrastination. Neff’s research indicates that individuals who practice self-compassion after a failure—treating themselves with the kindness they would offer a friend—exhibit greater motivation to improve and are less likely to repeat the mistake. Forgiveness, it turns out, is a more effective tool than willpower.

From this foundation of self-acceptance, effective, evidence-based strategies can be implemented. Many therapists use techniques from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to help patients identify and challenge the distorted thoughts that lead to avoidance, such as “This has to be perfect” or “I can’t handle this feeling.” Another approach is to shrink the task to a size that feels non-threatening. This is the principle behind the “two-minute rule,” popularized by the productivity consultant David Allen in his book Getting Things Done. The rule states that if a task takes less than two minutes to do, do it now. For larger tasks, the goal is to find a two-minute version to simply start. The objective is not to finish the task, but to break the initial wall of emotional resistance.

For Michael, the software engineer, progress began not with a perfectly organized Asana board, but with a commitment to work on his most dreaded task for just five minutes. “The first few times, I’d just sit there for five minutes, feeling the dread,” he admits. “But then, one day, the five minutes ended and I just kept going. Not for long, but it was a start.” He learned to acknowledge the feeling of static without letting it dictate his actions. He still procrastinates, but the periods of paralysis are shorter, the guilt less consuming. He is learning to manage the deadline within.

Our collective struggle with procrastination holds up a mirror to our societal anxieties. In a culture that fetishizes productivity and demands constant optimization, the act of putting things off can feel like a personal moral failure. Yet it may also be a quiet rebellion against overwhelming pressure, a human cry for rest in a world that never stops. To understand procrastination is to understand our complicated relationship with work, with failure, and with ourselves. The solution may not lie in becoming perfectly efficient machines, but in becoming more forgiving humans, capable of starting again, and again, right where we are.