The Echo in the Room: Why We Replay Our Relationships

The fight between Clara and Ben always begins with a rupture in the fabric of the ordinary. This time, it’s a carton of milk. Ben forgot to pick one up. When Clara opens the refrigerator to find it empty, the ensuing silence has a weight she knows all too well. It is the sound of a familiar script about to be read aloud.

Have you ever felt trapped in the same argument, wondering why you keep having the same fight? You know the lines by heart. You can feel the emotional crescendo coming. Yet, you seem powerless to stop the performance. For Clara and Ben, the curtain has just risen.

“I asked you this morning,” she says, her voice quiet but taut.

“I know, I’m sorry. It was a crazy day, it just slipped my mind,” Ben replies, already retreating.

The storm that follows is never about the milk. The milk is simply the cue. Clara’s frustration quickly escalates into a broader lament: “I feel like I’m managing everything alone.” Her voice rises, a desperate pursuit for connection. Ben, in turn, plays his part. He hears an attack, feels inadequate, and shuts down. “You’re blowing this out of proportion,” he says, turning away.

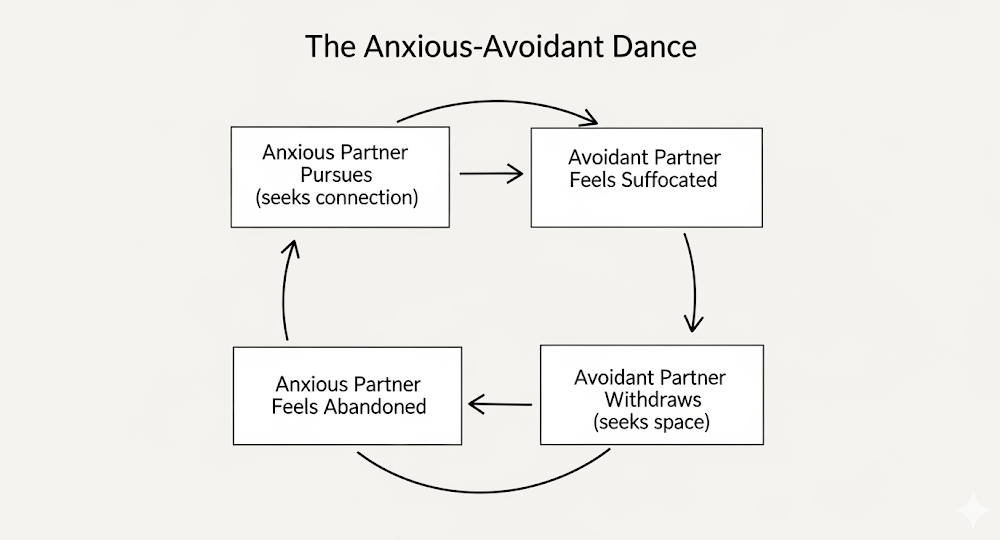

What follows is the painful choreography of their recurring dance. She pursues, he withdraws. The fight ends, as it always does, not with a resolution but with an exhausted cease-fire, leaving both of them feeling profoundly alone.

This sense of being haunted by a recurring pattern is one of the most bewildering aspects of intimate relationships. It’s not just about cyclical arguments. It’s also the unnerving realization that the person you just fell for bears a striking resemblance to the one who broke your heart years before. Why do we find ourselves in different settings, with different people, playing out the same scenes?

The answer lies in scripts written in childhood that we unconsciously perform for the rest of our lives. To understand the echo in the room, we must look at the architecture of our own hearts, an architecture laid down long before we ever knew what love was.

The Blueprint of Attachment

The most powerful framework for this is Attachment Theory, pioneered by psychoanalyst John Bowlby. He found that our first relationships with caregivers create a powerful blueprint—an “internal working model”—for how we view ourselves and others. This model, formed in infancy, dictates the steps of our relational dance as adults. Our partners become our primary attachment figures, the people we turn to for safety and comfort.

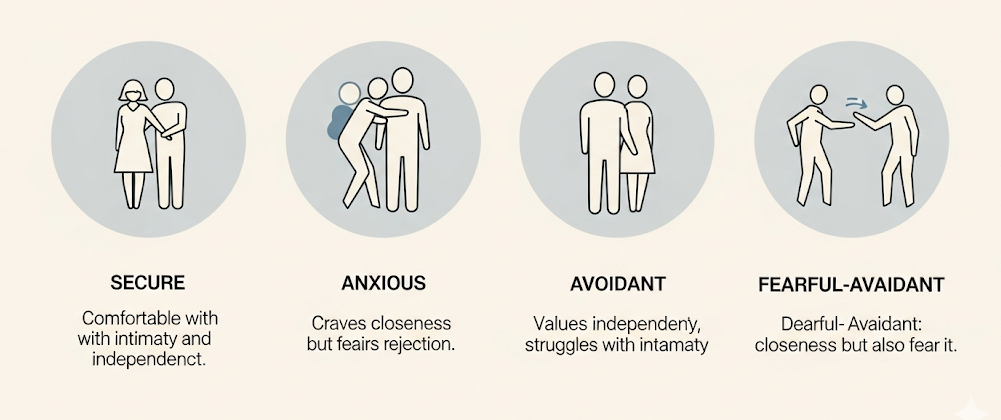

While many people develop a secure attachment style, finding it easy to trust and connect, a significant portion of the population develops insecure styles due to less consistent early caregiving. The two most common in relationship conflicts are Anxious-Preoccupied and Dismissive-Avoidant.

The Anxious-Preoccupied Partner

Often the product of inconsistent caregiving, this person lives with a deep-seated fear of abandonment. As an adult, they are hyper-vigilant to any sign of distance. A late text message or a forgotten carton of milk can feel like a primal threat to the relationship. To manage this anxiety, they pursue connection, sometimes through what are called “protest behaviors”—picking a fight, for instance, just to get a reaction. This is Clara.

The Dismissive-Avoidant Partner

This person likely grew up in an environment where emotional needs were discouraged. They learned that self-reliance was the safest path. As adults, they are fiercely independent and uncomfortable with too much emotional closeness. When a partner becomes demanding, their attachment system “deactivates.” They pull away, suppress their feelings, and seek safety in distance. This is Ben.

The Anxious-Avoidant Dance

The tragedy of this pairing is that each partner’s coping mechanism is the other’s greatest trigger. The more Clara pursues out of fear, the more Ben withdraws to find safety. His withdrawal confirms her fear, compelling her to pursue more frantically. They are caught in a feedback loop, a destructive cycle that leaves both partners feeling utterly misunderstood.

The Lure of the Familiar

But why are we drawn to these patterns in the first place? We aren’t drawn to partners who are necessarily healthy for us, but to those who feel familiar. Our brain matches the emotional signature of our childhood, because it feels like “home”—even if home was a place of anxiety.

Consider Maria. She is a successful, vibrant woman who consistently dates emotionally unavailable men. Her partners are often charming but noncommittal, brilliant but self-absorbed, or struggling with issues that make them incapable of true partnership. Her friends are bewildered. But Maria’s father was a beloved but distant figure, a man she adored but could never quite reach. Unconsciously, she is re-enacting this early scenario, driven by what psychoanalysts call “repetition compulsion.” The subconscious hope is, “This time, I will make him stay. This time, I will win the love I never got.” She isn't choosing a future; she is trying to fix her past.

How to Break the Cycle: First Steps

Recognizing these deeply ingrained patterns can feel disheartening, but awareness is the first step toward change. Breaking free is challenging, but not impossible. It requires moving from unconscious reaction to conscious choice.

Here are a few actionable first steps:

- Name the Dance. The next time you find yourself in the familiar conflict, try to mentally step back and label what's happening. Simply thinking, “This is our anxious-avoidant pattern again,” can create enough psychological distance to break the immediate reactive cycle. You don't have to solve it; just notice it.

- Identify the Real Fear. Look beneath your surface-level anger or silence. Are you, like Clara, truly afraid of being abandoned or feeling unimportant? Or are you, like Ben, afraid of being seen as a failure or feeling suffocated? Identifying the primary attachment fear is key. Try writing it down for yourself: "In this moment, I am afraid that..."

- Use a Simple Script-Changer. When you're ready, try voicing this underlying fear instead of the usual accusation. A simple formula can be: "When you [do the behavior], the story I tell myself is [your fear], and I feel [your emotion]." For example: "When you forgot the milk, the story I tell myself is that I'm not on your mind, and I feel scared and alone." This is not about blaming; it is about revealing.

- Seek a New Blueprint. Learning about your own attachment style is empowering. Resources like the book Attached by Amir Levine and Rachel S.F. Heller can provide a clear and accessible starting point. For deeper work, evidence-based approaches like Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) are specifically designed to help couples reshape these patterns.

The echo in the room may never disappear completely. But with compassionate awareness, we can learn to recognize it for what it is—a ghost from the past—and choose not to let it dictate our present. We can learn to stop the dance and begin a new conversation, one where the forgotten milk remains just that, and the real discussion is about the fundamental, human need to know that we are safe, that we are loved, and that we are not alone.