Why We Feel Lost in an Age of Infinite Choice

Ellie stood before the floor-to-ceiling window of her new apartment, looking out over the city she had spent the better part of a decade conquering. The apartment, modest but hers, was the last and most significant item to be crossed off her life’s checklist. To own a space that was entirely her own before thirty—this goal had been a lighthouse, guiding her through countless late nights at the office and frugal weekends. She had made it. The echo of her housewarming party had just faded, the congratulations of friends still hanging in the air. But now, in the quiet, an emotion she had never anticipated began to fill the room. It wasn’t joy or pride. It was a vast, cavernous emptiness.

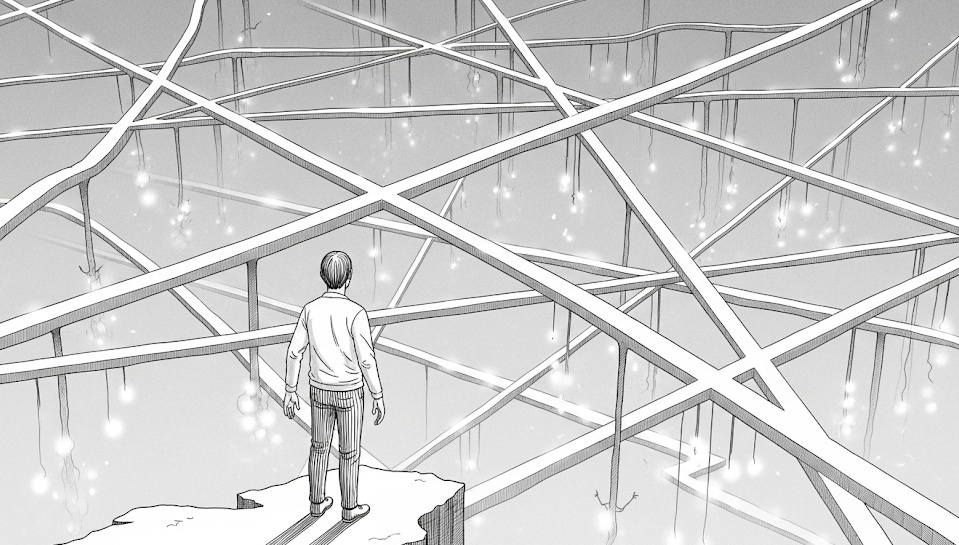

The goal had been achieved. What now? The lighthouse that had guided her was extinguished, leaving not a promised land, but a vast, chartless ocean.

Ellie’s feeling is not an isolated case. It is a quiet epidemic of our time. We are living in an age of unprecedented possibility. With a tap on a screen, we can choose a new career, a new partner, a new way of life. We have been told that happiness is a multiple-choice question, and we have been handed the longest list of options in human history. Yet, a profound paradox is unfolding: in an age where we can have anything, why do so many of us feel like we have nothing, our inner lives defined by a sense of being lost and empty?

The Paradox of Choice and the Tyranny of "Should"

In his book The Paradox of Choice, sociologist Barry Schwartz argues that an overabundance of options, far from making us freer or happier, leads to widespread anxiety and decision paralysis. Every choice we make is haunted by the ghosts of the possibilities we’ve abandoned. We are terrified of choosing “wrong,” of missing out on the optimal path to a perfect life. As a result, we walk every path with hesitation, an inner voice constantly asking, “Would the other road have been better?” This Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) turns us into distracted tourists in our own lives.

At the same time, society, family, and social media have woven for us a standard blueprint for a “successful life.” We are held captive by a subtle but powerful set of “shoulds.” You should get a stable, high-paying job. You should get married by a certain age. You should present a life as polished as the ones curated in your Instagram feed.

Many people, like Ellie, become incredibly efficient at executing the goals laid out by this external blueprint. They are excellent performers. But they rarely get the chance to stop and ask the most fundamental question: “Is this what I truly want?” When we live according to this external template for too long, a chasm forms between our daily actions and our inner, core values. Life ceases to be an authentic experience and becomes a passive exercise in meeting expectations. We spend our days playing the role of a successful, socially-approved person, but we feel like an actor whose soul is absent from the stage. This disconnection from our authentic self is the most fertile ground for emptiness to grow.

The Existential Vacuum: When the Old Maps No longer Work

This modern sense of being lost has deeper roots. The psychoanalyst Viktor Frankl, a survivor of Auschwitz, introduced the concept of the “existential vacuum” in his seminal work, Man’s Search for Meaning. He argued that the fundamental human drive is the “will to meaning.” In the past, traditional structures—religion, community, collectivism—provided ready-made maps of meaning. They told people what to believe, how to live, and what life was for.

In modern society, however, these traditional anchors have largely dissolved. We are no longer dictated to by instinct, like animals, or by tradition, like our ancestors. We have been granted unprecedented freedom, but we have also been cast into a vacuum of meaning, with no pre-written script. As Frankl wrote, modern man does not know what he must do or what he ought to do, and the result is that he often doesn’t even know what he truly wishes to do.

This existential vacuum manifests in various ways: as boredom, apathy, burnout, or a pervasive feeling that “nothing really matters.” To fill this void, people may frantically pursue power, pleasure, or wealth, or blindly conform to the expectations of others. But these external fillers can never satisfy the deep, internal hunger for meaning. They are like saltwater; the more you drink, the thirstier you become.

The Burden of Freedom: The Responsibility of a Self-Authored Life

The existential psychologist Irvin Yalom deepened this insight. He proposed that our anxiety stems from our awareness of the four “ultimate concerns” of human existence: death, isolation, meaninglessness, and, most crucially, freedom.

Freedom sounds like a gift, but it is also a heavy burden. Because on the other side of freedom lies inescapable responsibility. When we realize that the universe has no pre-ordained script for us, that no higher authority can give us the ultimate answers, it means we must take full responsibility for our own choices, our own lives, and our own meaning.

This responsibility is terrifying. It means we can no longer blame our unhappiness on fate or others. We are the sole authors of our existence. This awareness often triggers a profound anxiety. To escape the weight of this freedom, we might choose to hand our lives over—to a charismatic leader, to a rigid ideology, to a set of social rules. We prefer to live in a secure, if unfree, cage with clear instructions rather than face the open, uncertain wilderness of true freedom. This also explains why choice can be so paralyzing—because every choice is an act of defining who we are, a creative act so profound it can feel staggering.

Charting a New Course: Creating, Not Finding, Meaning

So, if the old maps are obsolete, how do we navigate this wilderness of meaning? Frankl’s answer was revolutionary: the meaning of life is not something we find, like a lost object. It is something we create and fulfill. Meaning doesn't exist out there somewhere; it exists in our response to each and every moment.

He suggested three primary pathways through which we can create meaning:

- By Creating a Work or Doing a Deed: This does not refer only to great art or grand causes. It can be found in pursuing excellence in your job, in contributing to your team, in carefully tending a garden, or in cooking a meal for your family. Any act that invests our energy into the world and adds value to it can be a source of meaning.

- By Experiencing Something or Encountering Someone: Meaning can also be discovered in profound experiences. It can be found in immersing oneself in the beauty of nature, being moved by a piece of music, or, most importantly, in loving another person. To truly see, understand, and care for another being allows us to transcend our own limitations and find profound meaning in connection.

- By the Attitude We Take Toward Unavoidable Suffering: This is Frankl's most profound insight. Even when faced with a fate we cannot change—such as an incurable disease or a great loss—we are left with the last of the human freedoms: the ability to choose our attitude in any given set of circumstances. The courage, dignity, and compassion we display in the face of suffering is, in itself, one of the highest forms of meaning creation.

This echoes the findings of psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan in their Self-Determination Theory. They discovered that all humans have three innate psychological needs: Autonomy (the need to feel in control of our own behaviors and goals), Competence (the need to feel capable and effective), and Relatedness (the need to feel a close, authentic connection to others).

When we feel lost and empty, it is often because one or more of these fundamental needs has been chronically unmet. Are we in a job where we feel we have no say (lacking Autonomy)? Have we stopped learning or challenging ourselves (lacking Competence)? Are our social lives wide but shallow, leaving us without deep connection (lacking Relatedness)?

From this framework, the path out of emptiness becomes clearer. It is not about finding one grand, overarching “purpose of life.” It is about beginning to consciously and intentionally nourish these three basic needs in our daily lives.

Conclusion: From "What's Next?" to "What Now?"

Let us return to Ellie, standing at her window. The emptiness she felt was not a sign of failure, but an invitation. An invitation to shift her focus from the pursuit of external goals to the exploration of her internal world. The question that haunted her, “What’s next?” can be replaced by a gentler, yet more powerful one: “What now?”

What now, in this apartment that is mine, can make me feel a genuine connection (Relatedness)?

What now, can I learn or try, no matter how small (Competence)?

What now, is a choice that feels more true to myself, and not just to a checklist (Autonomy)?

The meaning of life is not the ultimate treasure found at the summit after climbing one mountain after another. It is more like the deep connection you build in the valley, with every step—the connection to the earth beneath your feet, to the companions by your side, and to the wind on your face. It is not an answer to be found, but an ongoing conversation to be had. A sincere conversation with the world, and with the deepest parts of ourselves. In that conversation, emptiness is not the end of the road. It is the beginning of the path. The path to a life that is truly your own.